The gloves come off

While the country has been fixated on the tensions between the Democratic Alliance and ANC regarding the proposed budget, a similar battle has occurred between the two parties on the communications and technology front.

Since stepping into office as South Africa’s new Minister of Communications and Digital Technologies in June 2024, the DA’s Solly Malatsi has had his plate full.

Several high-priority matters demanded immediate attention, including the financial disasters at the SABC and Post Office, South Africa’s failed digital TV migration, and switching off 2G and 3G in South Africa.

Starlink was another such prominent issue. The satellite broadband operator had deprioritised its launch in South Africa over BEE ownership concerns. Despite that, many people had already started using the service.

Malatsi has taken action to tackle several of these issues but has been met with fierce resistance in Parliament from portfolio committee chairperson Khusela Diko, who is also an ANC member.

The first point of conflict between the two was when Malatsi withdrew the controversial South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) Bill before its second reading in Parliament.

Malatsi said the Bill was “insufficient” to aid the deteriorating state broadcaster, as it did not address how the SABC would be funded, considering that most South Africans are refusing to pay their TV Licences.

Malatsi also took issue with the Bill granting the minister additional powers over appointing the broadcaster’s board.

His predecessor, Mondli Gungubele, introduced the Bill into Parliament in October 2023, which he said was based on inputs from key industry stakeholders — including the SABC itself.

Diko immediately criticised Malatsi’s decision to withdraw the Bill, saying it would be the death knell for the ailing state broadcaster.

Although she initially acknowledged his executive authority to do so, she soon changed her view when President Ramaphosa clipped his cabinet’s wings following Malatsi’s action.

“While appreciative of the fact that as the executive authority, the minister may rescind the Bill for whatever reason before its second reading in the House, the chairperson holds that this decision by the minister would be highly ill-advised,” Diko said in early November.

Gungubele, also an ANC member and Malatsi’s deputy, echoed Diko’s position that withdrawing the Bill would render years of effort worthless, and the Parliamentary process would have to begin again.

Instead of withdrawing the Bill, Diko and Gungubele argued that it should be amended before being assented to.

Malatsi remained steadfast in his decision to withdraw the SABC Bill, which resulted in the Presidency issuing a directive that cabinet ministers may not withdraw pending legislation without permission.

From now on, Ministers must first seek permission from President Cyril Ramaphosa and Deputy President Paul Mashatile before they can withdraw Bills.

This led to the speaker of the National Assembly, Thoko Didiza, refusing to gazette the withdrawal of the SABC Bill while the DA and ANC fought over whether the new directive could be retroactively applied.

According to Diko, this has allowed the portfolio committee to continue working on the Bill in 2025, with a plan to complete it by mid-year.

The Starlink schism

Another responsibility of the communications portfolio is expanding universal Internet access, which Malatsi has said is key to allowing South Africans to participate in the digital economy.

Although South Africa’s broadband population coverage is over 99%, thanks to the expansion of mobile networks, many households and businesses in remote locations remain underserviced.

Many cellphone towers also remain susceptible to load-shedding, vandalism and theft, making satellite-based services like Starlink invaluable in remote areas.

Starlink uses low-earth orbit (LEO) satellites to provide Internet connections in even the most remote areas of the world.

It has become popular by offering faster speeds at lower prices compared to established geostationary satellite broadband providers.

Starlink, owned by SpaceX, had initially planned to launch in South Africa in 2021 but put these plans on ice when the industry regulator Icasa amended laws governing black ownership of network operators.

Although SpaceX initially did not confirm this regulatory change caused it to halt its South African plans, well-placed industry sources said they were the reason Starlink deprioritised the country.

To encourage Starlink and other international players to enter the market, Malatsi plans to introduce equity equivalence investment programmes (EEIPs). However, Diko is having none of it.

“Minister Malatsi should know that when it comes to transformation in the ICT sector, the law is clear on compliance and that cutting corners and circumvention is not an option — least of all to appease business interests,” Diko said in a recent statement.

“It appears his proposed directives and regulations are an attempt to undermine empowerment legislation by stealth and, should this be found to be the case, they will be fiercely opposed.”

She also argued that Malatsi’s fixation on EEIPs is to specifically encourage Starlink to enter South Africa, saying that the minister must seek an amendment to the law if he is “unhappy with the 30% ownership rule.”

Malatsi responded to Diko in a statement arguing that EEIPs are permissible by law in South Africa and have been used in other parts of the economy to attract international investment, such as in the automotive industry.

“Recognising their potential, the government’s Medium-Term Budget Plan, formally approved by Cabinet, has adopted the introduction of EEIPs in the Information and Communications Technology sector,” he added.

Battle over the State IT agency

Malatsi and Diko have also butted heads regarding regulatory changes involving the State Information Technology Agency (Sita).

The minister recently proposed amending the regulations governing the agency after the Department of Communications and Digital Technologies determined that it cannot adequately fulfil its mandate.

The state agency’s current mandate requires all government departments to procure IT equipment and services from the agency.

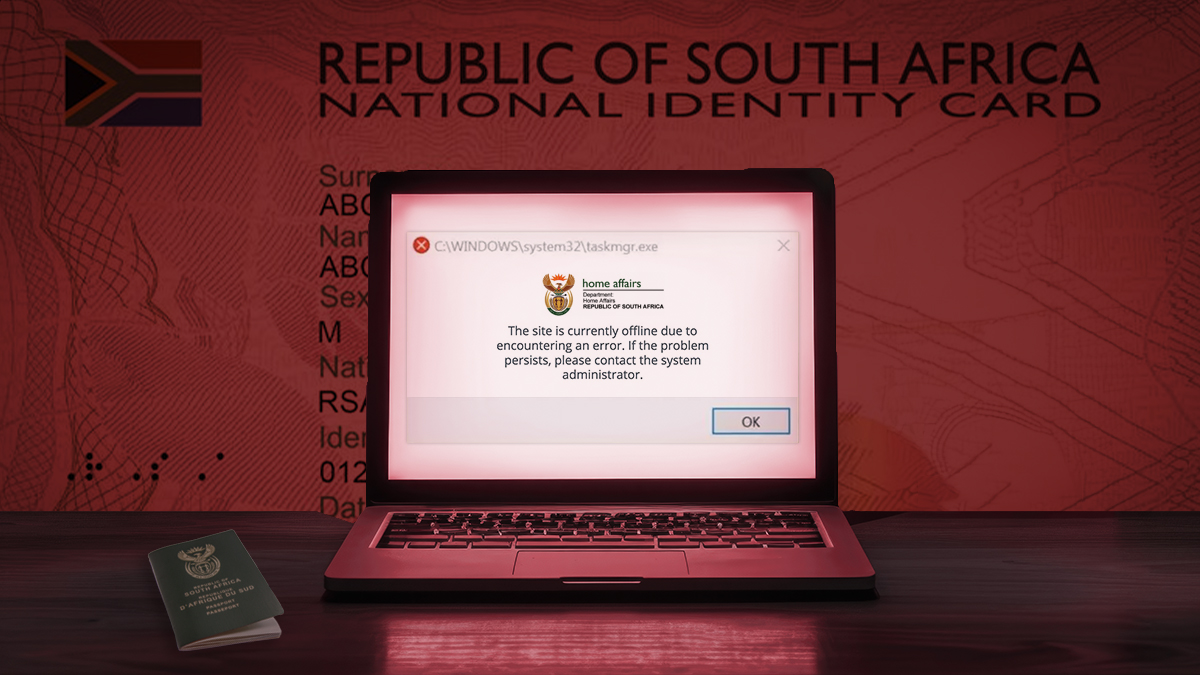

Malatsi’s rationale is to allow smaller departments to procure their own equipment and IT services, allowing Sita to better serve bigger departments such as Home Affairs.

However, Diko said the Sita Act does not empower the minister to alter any fundamental provisions and that several other solutions exist to bring stability to the agency.

These include appointing a new board and executive team to help Malatsi achieve his goals and automating the procurement system, which she said Parliament suggested.

Malatsi responded to Diko, saying that the proposed Sita regulations would allow departments to procure outside of Sita if they could provide a viable business case at a faster turnaround time and a lower cost.

He added that these proposed regulations have gained “overwhelming support from Ministers in the Government of National Unity” and are fully aligned with existing laws on government procurement.

“This flexibility can improve public services for all South Africans by ensuring that the government can respond faster and spend resources more efficiently, something which has been requested by several government departments for some time,” Malatsi said.